The ‘Unsolvable Myth’ of the Affordable Housing Problem: A Study on the Trajectory of Public and Social Housing Projects Throughout History, and an Analysis of the Problems “Solvability”

- Nicholas Clark

- 2 days ago

- 13 min read

Pictured above: The demolition of 3 of Pruitt Igoe’s 33 total building on June 15th. 1972. Demolition was complete by 1976.

Photo Courtesy of PD&R Edge Magazine

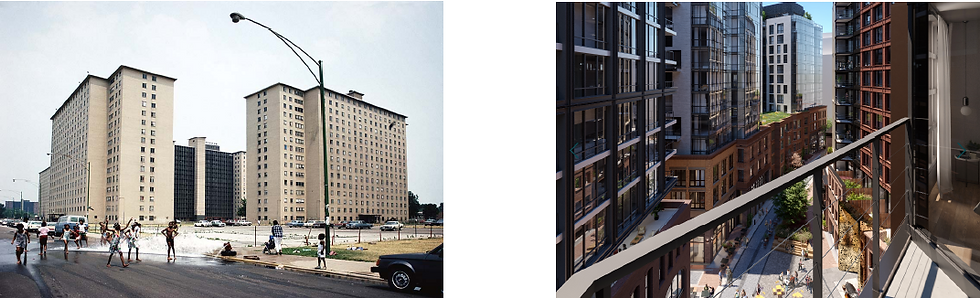

(Left) Robert R. Taylor Homes, Chicago, 1988 (Photo by Camilo J. Vergara, Courtesy Library of Congress (2014648586))

(Right) Entry Corridor of The Stacks in Washington DC (Photo Courtesy of thestacks.com)

A study of the history of the housing problem in the United States, this paper outlines 3 key chapters in that history to outline a trajectory of the issue. Beginning with the ‘Infamous Failures’ following World War II, the question is first asked whether these projects failed due to architectural issues or issues of discriminatory policy. In this section, the damage of how these failed projects were portrayed becomes evident. Moving a few decades forward, a ‘Shift in Trajectory’ is identified as the Hope VI Project put forward by the Clinton Administration has unforeseen impacts on what kind of housing projects become prevalent throughout the country. The public consciousness moves away from large-scale public and social housing for an incentivized preference towards gentrification. Finally, the modern zeitgeist is examined as a product of this trajectory, painting ‘A Hopeful Future’ of private high-density multi-family affordable housing projects and truly successful, reinvigorated public housing initiatives put forward by more social justice minded housing administrations.

Introduction

The social injustice of those who must live in an urban or socially affluent condition unhoused has existed for as long as social contracts themselves. A necessary result of this arrangement is the architectural, cultural, and political problem of enabling these groups to obtain housing within the societal framework they occupy. Focusing at first on the sense of the US in the last 80 years, housing the unhoused took off as a post-World War II endeavor. Over time, projects failed for reasons both known and avoidable, a narrative was crafted and fed to the public, policies made the challenge less approachable, and the housing problem is only now properly getting reapproached in the last 10 years. A side effect of the storied history of the problem has resulted in a thundercloud in the discourse of public opinion that the housing problem is somehow unsolvable. Over the course of this paper, the argument will be made through a series of case studies and evident conclusions, marking a trajectory over the last 80 years, that the housing problem is, in fact, solvable in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The story of public and social housing initiatives in the U.S. begins around the time of World War II with the publication of Modern Housing by Catherine Bauer in 1934. The novel draws comparisons between the U.S. and European approaches to alleviating their respective unhoused populations. In the opening page, Bauer defines ‘Modern Housing’ as housing that which “provides certain minimum amenities for every dwelling: cross-ventilation… sunlight, quiet, a pleasant outlook… finally it will be available at a price which citizens of average income or less can afford.” (Bauer xv). This definition, while appearing easy enough to accomplish to the uninformed, has proved an idealistic utopian dream to those who have been thus far charged with the responsibility of realizing it. The influence of Bauer’s book on ways housing has been thought of in the last eight decades cannot be understated in a social and architectural context. America, which was not portrayed favorably in the publication, became obsessed with large-scale public housing initiatives to alleviate the problem in one fell swoop. Such an impact is apparent in the first set of case studies from 1951-1962 that defines the first era of housing projects post WWII; Those that were doomed to fail.

Case Study Set #1: Pruitt Igoe, St. Clair Village, and Cabrini Green

Infamous Failures

Pictured above: The demolition of 3 of Pruitt Igoe’s 33 total building on June 15th. 1972. Demolition was complete by 1976.

Photo Courtesy of PD&R Edge Magazine

In 1951, St. Louis, Missouri became another metropolitan city poised to tackle large scale public housing with ambition and promise. The 33 eleven-story building project promised a clean, safe, and well-kempt environment for those who had previously been banished to the slums of the urban core of St. Louis. In reality; however, it did not take long for this promise to feel empty to both the projects residents, and the broader St. Louis community. By 1960, only 5 years after the final Pruitt Igoe building was complete, a lack of funding, discriminatory racially motivated policy, and a vulnerable resident population created a culture of dilapidated violence that terrorized the low-income woman and children. By July 1972 the projects were condemned by the St. Louis Housing Authority and demolition began.

In the time since the failure of Pruitt Igoe, the St. Louis Housing Authority had pinned the failure on the residents being ‘unfit’ for the social requirements of ‘High-Rise living’. Other important voices of the time labeled the project as the great failure of Modern Architecture, as a vehicle to condemn the design style that didn’t have much to do with the true reasons for the projects' downfall. The clearer and more nuanced picture of Pruitt Igoe’s failure is an image of systematic discrimination, a lack of foresight with regard to maintenance funding, and a general disregard for the well-being of the population the project was attempting to help. Nevertheless, the narrative was crafted such that the public remained convinced that the failure was the fault of the residents until the release of ‘The Pruitt-Igoe Myth’ in 2012 by Chad Friedrich. The documentary sets the record straight through a series of personal interviews with the residents of the projects themselves, and exists today as the primary source of information on the development.

A protest at the Cabrini-Green demolition site, Nov. 6, 1995. (The Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum)

Not to be outdone by St. Louis; Chicago, Illinois endeavored to remedy the housing problem themselves in the Cabrini-Green Neighborhood. Cabrini-Green Homes, spanning over a longer period of time than the prior case study, was a housing initiative built in 10 sections over 20 years and was subjected to the ebbs and flows of American social housing sensibilities from 1962-1995. While having some similar problems to what plagued Pruitt-Igoe, Cabrini-Green lasted long enough to be impacted to the ill-fated HOPE VI policy initiative put forward by Bill Clinton, which spelled the beginning of the end for Cabrini-Green. Given the longer run of Cabrini-Green, in its history the development was more publicly advocated for by its residents.

The tension between the public and the government centered around the project’s potential redevelopment, and it’s inevitable demolition. The HOPE VI Program promised to be a reinvestment into the housing projects that had become dilapidated over the course of the last several decades. HOPE VI ended up placing an emphasis on private development and gentrification over the large scale public projects of the 50s and 60s.

An aerial shot of St. Clair Village in 1955. (Photo courtesy of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development Photographs, Deter Library & Archives, Heinz History Center)

Wrapping up the notable early housing projects in the 1900's U.S. is St. Clair Village in Pittsburgh, PA. St. Clair Village was in operation in Pittsburgh from 1955-2010 and during that time “Black residents were limited to 30 percent of units even if there were vacancies in the units reserved for white residents. The Housing Authority had difficulty filling these vacant units and received tremendous opposition from white residents. More than 400 white families withdrew their applications, citing opposition to integration” (Public Source). St. Clair Village made a lot of the same mistakes in its inception that Pruitt Igoe did. The difference being that with St. Clair, racial tension came both from white residents and housing decisions that were being made on the basis of race by the Housing Authority. Racial discrimination hindered the project on multiple fronts, leading to it’s eventually failure as a development. Once again, the obstacle in the way of ending homelessness is not a problem of the architecture, but a problem of discrimination and restrictive policy.

Takeaways from the first set of Case Studies

It is evident from looking at the beginning of the United States’ great endeavor into solving the Housing Crisis that it was everything but the architecture that got in the way of the projects put forward as a solution.

For Pruitt Igoe, a story of victimization of the very population the development was meant to help. A lack of maintenance and a cultivation of a culture of violence lead to the downfall of the project. For Cabrini Green, misguided policy and an improper use of funds created the circumstances under which the development was inevitably demolished by the Chicago Housing Authority. Finally, for St. Clair Village, a lack of consideration for the Sociocultural needs of the community as well as the lack of tolerance from other residents created an environment under which a successful housing initiative could not take place.

The title of this case study set ‘Infamous Failures’ speaks to the notoriety of these case studies within the historical zeitgeist of the Housing Crisis. As will become clearer later on in the paper, these particular failed projects inadvertently created the very myth this paper hopes to explore. It was publicly stated by the housing authorities and local governments associated with these projects that it was not their error, but an error of the residents and the architecture that cultivated the tragedies in occurrence at the site of these failed projects. These statements went on to perpetuate the idea within the architectural profession and the public eye that Affordable Housing was a ‘wicked’ problem that anyone with any sense of self-preservation wouldn’t go near with a 10-foot pole. Continuing to look forward through the historical trajectory of the problem; however, may very well indicate conclusions quite the contrary to the prevailing public opinion on the issue.

Case Study Set #2: Boulevard Gardens, Yessler Terrace, Robert Taylor Homes

A Shift in Trajectory

Aerial view of the Boulevard Gardens complex in development (Photo Courtesy of Getty Images)

The Boulevard Gardens complex built in Woodside, Queens in 1935 is a development that stands in evidence to the success achievable by affordable housing initiatives when not bogged down by misguided racial and socio-cultural policy. The Boulevard Gardens Housing Corporation was able to report after just 3 months that it’s low-rent model tenements with an average monthly rent of 11$ per room had all been leased (Karnik). The following year the New York State Board of Housing mandated that the complex prioritize low-income family residents by barring residents whose income was five times that of their annual rent and Boulevard Gardens reserved their housing accommodation accordingly.

In 1987 Boulevard Gardens transitioned out of being a low-income family residence to providing co-ops for shareholders but its 52 years as an affordable housing initiative serve as a lesson for future endeavors into remediating the Housing Crisis.

The rear or south facade of 717 Washington can be found in this detail of a panorama taken from the roof of the Marine Hospital on Beacon Hill. (Photo Courtesy of Lawton Gowey)

Yessler Terrace, completed in 1941, was Seattle, Washingtons first public housing development and was also the first racially integrated housing development in U.S. History. The site contains 561 residential units distributed among 68 two-story row house buildings. As a result Yessler Terrace takes on a much different visual profile from many of the previous case studies, appearing more suburban in contrast with the tall high-rise developments of New York, St. Louis, Pittsburg, and Chicago. Yessler Terrace is also one of the few developments looked at thus far that is still providing housing to more than 1,100 residents. In fact, a 1.7 billion dollar redevelopment initiative began in 2013 and is anticipated to be complete in 2028. (Seattle Housing Authority)

Yessler Terrace and Boulevard Garden serve as evidence to the notion that with enough investment and care from the community, large scale successful public housing initiatives are completely possible and obtainable for metropolitan communities.

Robert R. Taylor Homes, Chicago, 1988 (Photo by Camilo J. Vergara, Courtesy Library of Congress (2014648586))

Robert R. Taylor Homes in Chicago is known for having been the most ambitious public housing initiative in the world with 4,349 units holding a total of 27,000 people at it’s height in 1965. Constructed from 1959-1963 the project named after Robert Rochon Taylor (the first black chairman of the Chicago Housing Authority in 1942.) was a part of a massive federal urban renewal program to eliminate slum neighborhoods.

Similar to Pruitt Igoe, the ambitious project made a mistake in that it reinforced racial segregation as most of the housing was concentrated in black neighborhoods because of the general hostility from white communities regarding residential desegregation. While the name of the homes are after a pioneer of racial equality, it had precisely the opposite impact on the African American residents by relocating much of the pre-existing poverty and racial isolation the community was already experiencing. The development removed families from needed social services and the location of the buildings encouraged an increase in crime.

Robert R. Taylor Homes serves as a reminder that even though some projects began to see success in the later decades of the 1900’s, Public Housing remained a typology hindered by discriminatory policy and poor socio-economic policy.

Takeaways from the second set of Case Studies:

As the trajectory of the Housing Crisis shifts towards the end of the 20th Century, public and social housing project become more of a mixed bag of successful and unsuccessful projects, some of which persist in housing low income families to this day. Although the failed projects from the first set of case studies loom in the vision of public perception, it becomes apparent that the reality of the situation is far more nuanced. For Boulevard Gardens, a smaller scale success that eventually refocused to other residential demographics shows what was achievable as early as the 1930’s. For Yessler Terrace, a more suburban typology continues to provide housing to the less fortunate to this day and its poised for improvement in the coming years. And for Robert Taylor Homes the obstacles that still exist today hinder the ambition of what could have been a truly inspiring development.

Over the course of the 20th Century, the Housing Crisis was tackled by most major metropolitan areas in the form of public housing initiatives of various scales. For a multitude of reasons, none directly involving architectural design, most failed and those failures were repackaged to the public as a failure of the architecture and the residential demographics they were attempting to house.

As the Housing Crisis enters the contemporary, it becomes the responsibility of the architectural profession to recognize political and socio-cultural nature of the problem and stretch ourselves beyond just design if progress is ever to be made. Examples of developments that endeavor to do just that are what our third and final set of case studies are comprised of.

Case Study Set #3: The Stack, Unite d’ Habitation, Quinta Monroy

A Hopeful Future

Entry Corridor of The Stacks in Washington DC (Photo Courtesy of thestacks.com)

The Stacks in Washington D.C. elucidate what that future might be. Breaking ground May 19th of 2022, The Stacks promise to be a development familiar to the urban fabric of D.C. but altogether different. Designed with an emphasis towards outdoor green spaces, economic inclusion, and short enough buildings to let natural light wash the ground in between, this kind of development could very well be the future of providing homes to the unhoused. While it remains difficult to know what the outcome of such a development may be when it has not yet finished construction, the forecast is an optimistic one.

Corner view of Unite d’ Habitation by Le Corbusier (Photo Courtesy of Le Corbusier Foundation)

Le Corbusier for all that he contributed to Modern Architecture, was a proponent of the concept of ‘mass housing.’ a notion certainly borrowed from in projects covered previously. Mass Housing, as Corbusier saw it, was an effective way to inclusively remedy the Housing Crisis with an efficient and successful vigor. Unite d’ Habitation in Marseilles, France is one

such example of this vision. From his standpoint outside the U.S. Corbusier was able to avoid some of the discriminatory turmoil present in the states when Unite d’ Habitation was constructed in 1952 (the same year as Pruitt Igoe). As such, Corbusier was able to create a housing project that is still effectively serving it’s purpose to this day.

Research Diagram of Quinto Monroy Housing development showing the ‘parallel’ housing model. (Photo Courtesy of Research Gate)

Facade of Quinta Monroy shown from the Courtyard further illustrating the parallel nature of the project. (Photo Courtesy of Cristobal Palma)

Quinta Monroy, a social housing project in Iquique, Chile, utilizes an innovative programmatic organization in which modular units are tiled in parallel and then wrapped around a rectangular courtyard which provides a central organization to the scheme overall. Constructed in 2003, the 5000 square meter development houses 100 families and built on a modest budget of just over 200$ per square foot. Quinta Monroy and Unite d’ Habitation are both case studies outside the U.S. for a very particular reason and their inclusion in this research is not unintentional. Housing Policy outside the U.S. is often more relaxed surrounding issues of funds and zoning in other developed western countries, and as a result these other nations are able to lead the way into whatever the future of public and social housing may bring.

Conclusions: What Can Architects Do Moving Forward?

To conclude, having conducted an analysis across a historical trajectory of housing projects both in the United States and internationally, it has become obvious that the housing crisis is a crisis with a solution that can be achieved. How that can be done appears to be a collaboration between makers of policy, local and federal housing authorities, and the architectural profession. Policy makers and housing authorities can start by undoing the damage done by a century and a half of discriminatory zoning and economic policy and housing through the reinvestment into and redevelopment of dilapidated communities and neighborhoods. This first step will not be accomplished easily however, as it will take advocacy, and measures to ensure accountability for the makers of policy and housing authorities by members of the architectural profession.

As mentioned earlier, it is imperative to the solution of the Housing Crisis, that architects and designers alike work together to encourage the development of inclusive policy and zoning regulations so that the design of spaces that benefit the human condition and create a livable standard for the lower class can even be possible.

Bibliography

Building Resources:

Pruitt Igoe, About the Film. (2015, May 23). The Pruitt Igoe Myth. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from http://www.pruitt-igoe.com/about.html

St. Clair Village, Timeline: Pittsburgh Housing Policy. (2018, June 6). Public Source. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://projects.publicsource.org/zoning_timeline/lead_timeline.html

Cabrini Green, Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2016, May 24). Cabrini-Green. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Cabrini-Green

Boulevard Gardens, Karnik, R. (n.d.). Welcome to Boulevard Gardens. Boulevard Gardens. https://ritikaka.github.io/Boulevard-Gardens-Final/

Yessler Terrace, Redevelopment of Yesler Terrace. (2023, February 6). Seattle Housing Authority. Retrieved May 7,2023, from https://www.seattlehousing.org/about-us/redevelopment/redevelopment-of-yesler-terrace

Robert Taylor Homes. Modica, A. (Ed.). (2009, December 19). Robert R. Taylor Homes, Chicago, Illinois (1959-2005). Blackpast. Retrieved May 7, 2023, from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/robert-taylor-homes-chicago-illinois-1959-2005/

The Stack, Inspired by DC, Yet Altogether Different. (2020, March 5). The Stacks. Retrieved May 7, 2023, from https://thestacks.com/

Unite d’ Habitation, Serie: Unite d' Habitation. (2019, March 21). Worldheritage.org. Retrieved May 7, 2023, from https://lecorbusier-worldheritage.org/en/unite-habitation

Quinta Monroy, Mangukiya, J. (2022, April 6). Quinta Monroy Housing Project by Alejandro Aravena: The Need for Simplicity. Rethinking the Future. Retrieved May 7, 2023, from https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/2021/08/09/a4832-quinta-monroy-housing-project-by-alejandro-aravena-the-need-for-simplicity/

Readings and Media Resources:

The Pruitt Igoe Myth by Chad Friedrichs, About the Film. (2015, May 23). The Pruitt Igoe Myth. Retrieved May 3, 2023, from http://www.pruitt-igoe.com/about.html

Modern Housing by Catherine Bauer, Bauer, C. (n.d.). Modern housing.

Urbanized by Film First, Film First (Director). (2017). Urbanized [Film]. Vimeo.

Defensible Space by Oscar Newman feat. Aylesbury Estate & Pruitt-Igoe, Newman, O. (Director). (1996). Defensible Space [Film]. Institute for Community Design Analysis.

Toward an Architecture by Le Corbusier. Le Corbusier. (1927). Toward an Architecture.

Comments